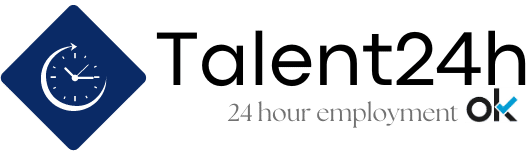

Scientists have discovered remnants long-lost of tectonic plates sunk deep into the Earth’s mantle, far from any known subduction zone, according to a pioneering study published in the journal Scientific Reports. The newly detected formations, which resemble ancient fragments of plates, are hidden beneath the center of continental and oceanic plates in regions where convergence of plates has never been documented. One of the most surprising examples was found under the western Pacific, baffling researchers who are wondering how these structures ended up so far from any tectonic boundary.

This discovery challenges long-held assumptions about the Earth’s internal dynamics. Previously, submerged plates had only been detected in subduction zones, where one tectonic plate dives beneath another. However, the new study, entitled “Full-waveform inversion reveals diverse origins of positive-wave velocity anomalies in the lower mantle”, uses a high-resolution method called full-waveform inversion to glimpse the hidden depths of the planet. Unlike traditional travel-time tomography, which relies on a limited set of easily identifiable seismic phases, full-waveform inversion processes complete seismograms, capturing subtle reflections and refractions that are often lost with conventional techniques.

Why the finding is so unexpected

The western Pacific anomaly, in particular, appears between 900 and 1200 kilometers deep, a region with no evidence of modern or ancient subduction. “It’s like discovering an extra artery in the human body using more powerful ultrasound,” said Professor Andreas Fichtner, co-author of the paper and seismologist at ETH Zurich. “We have used many methods to map the Earth’s internal structure before, but we had never seen these mysterious remnants of plates.”

Since standard models assume that positive wave velocity anomalies (areas where seismic waves move faster) mostly indicate cold tectonic plates descending into subduction zones, finding them beneath the interiors of stable plates is a surprise. “With our new high-resolution model, we see anomalies everywhere in the mantle,” said doctoral researcher Thomas Schouten. ”But we still can’t say exactly what they are. They could be fragments of archaic plates, delaminated lithosphere, or chemically unique deposits that have survived since the Earth’s formation.”

Inside the Earth’s deep layers

The Earth is divided into crust, mantle, outer core and inner core. The crust, where we live, has a depth of between 24 and 70 kilometers, while the mantle extends another 2900 kilometers, composed of semi-solid rock subjected to crushing pressure. Beneath that, the outer core of liquid iron and nickel is approximately 2,000 kilometers thick, swirling at temperatures close to 10,000 degrees Celsius. At the center, the solid inner core, also made of iron and nickel, reaches temperatures comparable to the surface of the Sun. Scientists monitor how seismic waves travel through these layers to identify changes in composition or temperature, much in the same way that doctors use ultrasound to examine tissues inside the human body.

What puzzles researchers the most

Despite the best imaging tools, scientists are not sure how these hidden anomalies arrived at their current locations. One possibility is that they have been there since the early days of the Earth, trapped as “primordial” pockets of chemical material. Another hypothesis is that they represent the delaminated base of the ancient lithosphere that broke off and sank into the mantle long ago. “We need more data to find out why these anomalies appear so far from the subduction zones,” Schouten explained. “It is possible that convection currents or even local chemical differences have guided them to these unusual points.”

Implications for global geology

If these anomalies were once part of the Earth’s plates, current ideas about subduction rates and mantle circulation may need to be reevaluated. The researchers previously used travel time tomography to correlate fast-wave velocity anomalies with ancient subduction zones, reconstructing plate movements over hundreds of millions of years. However, the presence of large anomalies where no subduction occurred complicates such reconstructions. “It suggests that not all fast anomalies come from subducted plates,” Fichtner said. “They could be much more diverse than we thought.”

What’s next for planetary science?

Researchers hope that future studies will determine whether these anomalies are really remnants of ancient tectonic plates, chemical deposits from the formation of the Earth or completely new types of underground structures. Some speculate that they could influence volcanic activity or heat flow in as yet unrecognized ways. As imaging techniques evolve, scientists will be able to better understand how these “sunken worlds” beneath the mantle shape the geological history of our planet.

“Each new snapshot of the Earth’s interior brings another surprise,” Fichtner added. ”What we are seeing now indicates that the mantle’s tapestry is richer and more complex than we ever imagined. We are just beginning to discover all the hidden threads.”

Stay tuned and informed thanks to the section where you will see other news related to science and that you can find from this own digital newspaper.